New Mexican National Guard Cracks Down on Border Crossings

The deployment of federal troops along the Suchiate River has brought the region’s informal trade and migration routes to a sudden stop, leaving coyotes and local merchants in limbo.

By Hannah Raslan

CIUDAD TECÚN UMÁN, Guatemala — It is an unusually quiet day at the principal border crossing between Guatemala and Mexico. Crossing guides, known as coyotes, linger on the riverbed, fixing their rafts, trading jokes, and waiting for someone in need of their services. These men transport goods and people across the Suchiate River for a modest fee of $1–2 each way. Usually, the work is steady.

But this week, silence reigns.

Just weeks ago, the Mexican government unveiled its new National Guard—a federal force composed of police and military units, designed to combat unlawful immigration along the country’s porous southern border. Since its deployment, life along the Suchiate has changed dramatically.

A Force Built to Block the River

“Normally we’d have people lined up,” said Manuel Espinoza, who has worked here for over a decade. “Now, nothing.”

The military operation has brought the informal economy at the river’s edge to a near standstill. Just upstream lies the pedestrian bridge—the official crossing between the two countries. Bypassing it by raft is technically illegal, but until now, Mexican authorities had largely turned a blind eye.

For decades, the Suchiate River has served as a key crossing point for asylum seekers fleeing their home countries, often headed to the United States by way of Mexico—a practice long criticized by U.S. officials, particularly under the Trump administration.

The decision by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to create the National Guard is widely seen as a response to mounting pressure from Washington to curb unauthorized migration.

Economic Shock for Border Communities

In the days following the announcement, thousands of troops poured into Chiapas, including hundreds deployed along the Suchiate. They were tasked with forming a human wall, sealing off more than 60 informal trails commonly used to cross. Officers were ordered to turn back anyone entering without formal permission—including Guatemalan merchants who had, for decades, moved freely between Tecún Umán and Ciudad Hidalgo.

Local vendors say their daily trade has plummeted, despite the fact that they were not the government’s intended targets.

Bribes, Rumors, and a River on Hold

Mexico’s armed forces have long battled a reputation for corruption. But López Obrador vowed this new force would be different, branding them “the incorruptibles” and “the hope of Mexico.”

Yet, according to Espinoza, cracks appeared within days.

“In the first few days, some of them were already taking bribes,” he says, referring to soldiers allegedly paid to look the other way during nighttime crossings.

Still, despite rumors of selective enforcement, the Guard’s arrival has had a chilling effect. Migration flows have slowed sharply while rafts sit tied up on the bank.

Part Two

“They Don’t Even Give Us Water”: Life in Mexico’s Migrant Bottleneck

Facing discrimination, disease, and deportation threats, Haitian asylum seekers describe life at the edge of Mexico’s broken immigration system.

TAPACHULA, Mexico — When Suleika Saint Louis arrived at the gates of Tapachula’s largest migration station, her four-year-old son was feverish, weak, and clinging to her shoulder. She had been waiting for months to apply for asylum in Mexico, surviving on sporadic food donations and a borrowed dime. Anticipation filled the air that night, as the National Migration Institute (INM) announced it would grant a fixed amount of visas after months of stalled applications.

Like hundreds of others, she pushed forward in the crowd outside Siglo XXI, Mexico’s largest immigration detention center. People screamed, shoved, and fought to secure one of the roughly 200 spots promised that night. With a push of luck, she made it into the building. Once inside, however, something felt wrong. Officials weren’t checking names or verifying identities as they usually did.

“I sensed something was off and I started panicking,” she said. “It wasn’t normal.”

Suleika shouted to be let out. An officer pulled her aside and quickly replaced her with another migrant from the crowd. Later that night, she learned the truth: those admitted were not being processed for humanitarian protection. They were boarded on a flight and immediately deported to Haiti.

“And I was going to be one of them,” she said, recalling the split-second decision that changed her life. “God got me out of there.”

A City Overwhelmed

Suleika and her family are among thousands of asylum seekers now stranded in Tapachula, the largest Mexican city along the country’s southern border with Guatemala. Once a transitory stop for migrants traveling northward, Tapachula has become a holding zone crowded with those unable to move forward and unable to return.

Just weeks earlier, in response to mounting pressure from the United States to reduce northbound migration, the Mexican government deployed National Guard troops across Chiapas and dramatically reduced the issuance of exit visas. These temporary permits had previously allowed migrants to transit through Mexico over the course of several weeks as they headed north to the U.S. border.

Now, with fewer legal options available, the asylum process is the only viable path forward for many. But the system is strained. Tapachula has absorbed the bulk of new arrivals, and the agencies responsible for processing claims—the INM and the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR)—are facing months of backlogs that have stretched the system far beyond its capacity.

Mexican law requires that asylum claims be resolved within 45 days, and that applicants remain in the state where they filed. In practice, wait times now often extend several months or more. In Tapachula, shelters are overrun, resources are depleted, and the streets are increasingly occupied by families living outdoors in makeshift camps.

No Way Forward, No Way Back

For Suleika, the standoff in Tapachula was just the latest hardship in a grueling journey. She left Haiti months earlier, fleeing both poverty and abuse. Originally from a town near the Dominican border, she worked in a Chinese-owned textile factory across the border in exploitative conditions.

“There was no food, no water, nothing,” she recalled. “They wouldn’t let you eat until late afternoon. They screamed at us in front of everyone.”

The breaking point came when she could no longer endure the mistreatment. She and her husband decided to leave, setting out for Mexico via a perilous route common among Haitian migrants: flying to South America, then traveling overland through countries including Colombia and Central America.

The most harrowing leg came in the Darién Gap, a stretch of jungle infamous for its violence, flooding rivers, and deaths. Suleika recounted seeing a young child fall off a cliff and die after slipping from his father’s shoulders.

“Many people died,” she said. “We saw children swept away in rivers. A Cuban man sat down to rest and never got up again.”

At one point, her husband nearly lost his footing on a cliff while carrying their son. Strangers rushed to help. “If he had fallen, that would’ve been it,” she said.

By the time she reached southern Mexico, she said, she was exhausted but still determined to continue. “I didn’t know it would be this hard,” she told me. “But I have to keep going.”

Camped in the Open

Now in Tapachula, the family lives in a makeshift camp along the roadside with dozens of others. Unable to find space in the city’s full shelters, they’ve pieced together a place to sleep using tarps, plastic sheeting, and borrowed materials. The family drinks from a nearby river, which Suleika said caused frequent infections.

Like many others, they have been unable to secure space in Tapachula’s overburdened shelters. One facility reported that 90 percent of its residents are now migrants waiting on asylum decisions. Others, unable to pay for a room in the city, have resorted to sleeping under tarps or in doorways. Their son, visibly unwell, had recently developed a fever, and Suleika was desperate for medicine. She said she had no money for treatment.

Each day, Evens walks into town in search of work. So far, he has been turned away at every opportunity. Suleika said that the National Guard does not typically harass them while they remain at camp, but entering the city has become increasingly risky. One of her friends was recently detained and deported while withdrawing money from an ATM in the city center.

“The people here don’t even give us water,” Suleika said, recalling the time she asked a nearby resident for some drinking water. “When we arrived, we didn’t have a single peso. We had a friend, a Haitian man who had been here longer. He gave us food so we could feed our son. If it were up to the people here, we would already be dead.”

Tensions Rising

Tapachula’s infrastructure was never designed to support a long-term migrant population of this size. The city lies in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state, where over three-quarters of residents live below the poverty line. Employment is scarce even for locals, and resentment toward the growing presence of migrants has become more visible.

Shelter staff reported a rise in xenophobic incidents targeting Black migrants, particularly Haitians and Africans. They said these groups are often met with suspicion by locals, and many face discrimination in hiring, citing both language barriers and anti-Black bias as contributing factors.

At the same time, staff noted that some Tapachula residents express sympathy for the migrants but are unable to offer support due to their own financial hardship. With many families struggling to secure consistent work or food, even those who want to help often cannot.

While some residents blame migrants for draining resources, advocates argue that the government’s failure to process asylum claims in a timely manner is the root cause of the current crisis. Without legal status, most migrants cannot leave the state, work formally, or access basic services. And with more people arriving each day, the pressure is growing.

A Long Road Ahead

Despite the conditions, Suleika said she still hoped to receive asylum in Mexico. Her plan had always been to continue north, but now, with her child sick and options limited, she was willing to stay if it meant safety and stability.

She said she often thought about her former life in Haiti—her job, her community, the long walks to work across the border—and wondered whether things would have been easier had she stayed.

“There are times I think I made a mistake,” she said. “But what can we do? We are still alive. We have to continue. We’ve already been through the worst.”

Part Three

Inside the Broken Asylum Process Under Remain in Mexico

Changing U.S. immigration protocols expose asylum seekers to a system difficult to comprehend.

TIJUANA, Mexico — When Talia Velazquez crossed the U.S. border with her toddler son in April 2019, she thought she was nearing the end of a journey. After fleeing gang threats in El Salvador and traversing Guatemala and Mexico, she had one plan: turn herself in at the border and request asylum.

It was the same path her sister had taken months earlier. She expected to follow her through the same process and reunite with her in Los Angeles.

But at the Calexico border crossing, instead of being taken through a legal asylum process inside the United States, Talia and her son were detained, held for four days in a detention facility known as “la hielera” (meaning icebox) and eventually returned to Mexico. Talia was left confused and without answers.

“They just said, ‘We don’t let people in anymore.’ I told them I had no one in Mexico. They didn’t care,” Talia said.

What Talia didn’t know—what most asylum seekers didn’t know—was that just three months earlier, the Trump administration had enacted the Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP, more widely known as “Remain in Mexico”. The policy, which upended decades of asylum law, required most non-Mexican asylum seekers to remain in Mexican border towns while awaiting court dates in the U.S., often months away.

In Talia’s case, that meant not only facing unexpected deportation to a country she had never lived in, but also navigating a changing legal system that offered little explanation and even less support.

A Journey Misunderstood

Talia left El Salvador under threat of death. Her husband, a police officer, had been targeted by gangs that operated with near impunity in their neighborhood. As the wife of a law enforcement officer, Talia feared she and her son were marked.

“There was no safe place to go within El Salvador. Wherever we ran, they’d find us,” she said.

She paid coyotes to help them cross two borders—into Guatemala, then Mexico—evading authorities and sleeping in ranches or safe houses. The trip lasted ten days. At the edge of Mexicali, she and her son ran toward the border on foot and turned themselves in.

At the time, she didn’t know her timing would determine everything.

“They told me, ‘If you had come two months ago, maybe we would have let you in.’”

The Return to Mexico

Before MPP, migrants who passed an initial credible fear interview were usually allowed to remain in the U.S. while their asylum claims were processed. But under MPP, this screening was effectively bypassed. Instead, most applicants were given court dates and returned to Mexico.

After days in freezing detention, without enough food, sleeping on the floor with only a foil blanket, Talia was given papers and told to sign.

She refused. She didn’t understand what she was signing and said she hadn’t been allowed to read it or offered translation services. She was sent back into detention. Hours later, she was removed from the cell anyway and placed in a group of women and children being deported back across the border.

“He told me ‘Sign here.’ I asked him what it was I was going to sign, because I didn’t know what I was signing. They didn’t give me the opportunity to read anything,” Talia asserts the agent didn’t explain the document further. “So I asked him what would happen if I didn’t sign it. ‘No matter what we’re going to turn you back [to Mexico],’ he tells me.”

Talia and six others were dropped off in Mexicali and given a humanitarian visa from the Mexican government, along with a date to appear in U.S. immigration court. They had nowhere to stay.

The others chose to return to their home countries, believing the process was futile. Talia stayed, hoping she’d still be able to present her case.

Immigration Officials Misreport Information

For asylum seekers placed into the “Remain in Mexico” program, the process is not just disorienting—it can be decisive. Those subjected to expedited removal and denied asylum by an immigration judge are barred from entering the United States for a minimum of five years.

Because of the severity of this consequence, U.S. law requires that immigration officers ensure migrants fully understand what is happening to them. According to Department of Homeland Security (DHS) guidelines, the burden is on the officer to be “absolutely certain... that the alien has understood the proceedings against him or her.”

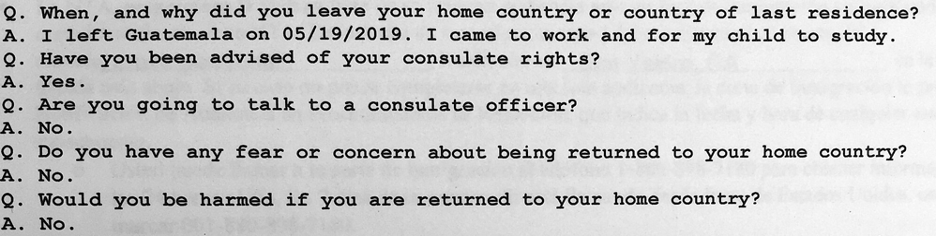

To this end, immigration officers use Form I-867, which documents the migrant’s biographical details and includes three “fear” questions:

- When and why did you leave your home country or country of last residence?

- Do you have any fear or concern about being returned to your home country?

- Would you be harmed if you are returned?

Migrants are expected to review this form, initial each page, and confirm that their answers are accurate. The form then becomes part of their official asylum record, and is often given significant weight by judges. But in practice, many migrants do not understand what they are signing—or what it means for their case.

For one, the form is in English, and translations are rarely provided. Migrants frequently sign without being read their answers, often under pressure, without legal counsel or a clear understanding of the stakes.

María Gómez, a 21-year-old Guatemalan woman, fled Escuintla with her son after her family was threatened by gangs. In her CBP interview, she says she explained her reasons for fleeing and her fear of returning. But when she showed me her signed interview transcript in Mexico, her responses told a different story.

I read her the original fear questions again in Spanish and asked her to answer them exactly as she had in the interview. Her answers—“Yes, I’m afraid,” “Yes, I would be harmed”—directly contradicted the written responses attributed to her. She was stunned. “I never said that,” she insisted.

Talia Velazquez also refused to sign. After four days in CBP custody with her son, a U.S. official told her she would be returned to Mexico. When he handed her a document to sign, she asked what it was. “They didn’t give me the opportunity to read anything,” she later recalled. “I asked what would happen if I didn’t sign. He told me, ‘Either way we’re going to turn you back.’”

Talia declined to sign and was placed back into the cold holding cell for the night. By the next morning, she was sent to Mexico anyway—without a signature, and without due process.

A growing number of asylum officers have publicly criticized the Remain in Mexico program for enabling these kinds of abuses. “CBP officers routinely fake paperwork,” one officer told a reporter. “Several times a week, I would speak to someone whose interview notes with CBP were wildly inaccurate, either intentionally or unintentionally.”

In many cases, migrants like María were told to sign sworn affidavits saying they did not fear being returned to their home countries, despite never having been asked the question.

Such practices were already a problem before MPP. A 2005 report from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) found that while 100% of asylum seekers signed required forms, 72% neither read their statement nor had it read to them.

Requests for legal assistance or translation services are frequently ignored or denied. Talia’s story reflects this breakdown. “We were lined up, and an officer told us we were going back to Mexico to wait for court,” she said. “I told him I didn’t sign anything. He just ignored me.”

Fear Bar Impossibly High for Exemption from Remain in Mexico

After four difficult days inside the Imperial Regional Detention Facility in Calexico, California, Talia was relieved when an official finally came to speak with her. She thought the worst of her journey was over—but she never expected what would happen next.

““I responded to all of [the migration official’s] questions,” Talia said. “And he comes and he tells me: ‘We are going to send you to Mexicali. You’re going to go back to Mexico and wait for your court date over there, to see if they let you in or not.’”

She remembers the moment clearly.

“And I tell him, ‘But how? I don’t have family in Mexico.’ I had told him that I have a sister in Los Angeles who could receive me.”

But the officer was unmoved.

“He says, ‘Now we’re not going to let you come in because we aren't letting anyone in anymore. If you had come two months ago, maybe we would have let you in then.’”

Talia grew more desperate.

“I tell him: ‘But where are you going to leave me? I don’t have money. Besides, who am I going to stay with? I’m not familiar with Mexico, it scares me here.’”

She says he just shrugged.

“‘Go back how you came,’ he tells me.”

“I only had 20 pesos—about a dollar—on me. ‘I can’t,’ I tell him.”

The fear screening process under MPP has been heavily criticized for failing to protect asylum seekers like Talia, who voiced her fears yet was returned anyway.

In June 2019, just five months into MPP’s implementation, the labor union representing asylum officers filed an amicus brief with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, challenging the legality of the program. The officers argued that MPP lacked safeguards necessary to prevent wrongful returns and that the policy forced them into “situations where [they] might be required to violate the law.”

According to the brief, the process “all but ensures violation of the non-refoulement obligation.”

One major concern is that asylum seekers must affirmatively state their fear of returning to Mexico for a fear screening to be triggered. Officers are prohibited from asking first. Yet, as the brief notes, fear of return is “not something most asylum seekers... would volunteer” while in custody or under duress.

The union and multiple human rights organizations have condemned this practice, calling it unrealistic and unjust. Requiring asylum seekers to explicitly request a protection they may not know exists effectively guarantees that many will be wrongly returned. Many of those denied a fear screening, the brief states, belong to groups known to face high levels of persecution in Mexico.

Even when individuals do express fear, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents have sometimes failed to refer them for the required interviews. In Talia’s case, despite clearly stating she feared returning to Mexico, no screening was ever offered.

A study by the U.S. Immigration Policy Center at UC San Diego found that six in ten asylum seekers who expressed fear of return were placed into MPP without undergoing a fear screening, which directly violates U.S. obligations under international law.

Even for those granted an interview, the standard of proof is exceptionally high. Asylum seekers must demonstrate that they are “more likely than not” to face persecution or torture in Mexico–a threshold typically used in full court proceedings with legal counsel, access to evidence, and the right to appeal.

Under MPP, none of those protections apply.

As the asylum officers’ brief explained, “This mismatch between the high evidentiary standard and the inadequate procedures all but ensures violation of the non-refoulement obligation.”

A 2019 investigation by U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley’s office echoed this concern, finding that the “more likely than not” standard made it “virtually impossible” for asylum seekers to qualify for exemption, even when they faced grave and documented danger in Mexico.

“All We’re Asking For Is Safety”

After her forced return to Mexico, Talia eventually made it to Tijuana with the help of her brother-in-law, who had U.S. residency and could cross the border. There, she stayed in a shelter, afraid to go outside, waiting for court dates that offered no resolution.

She had attended multiple hearings by the time we spoke. Each time, the judge declined to allow her to enter the U.S. while her case was pending. She had submitted proof of threats against her family, of her husband’s police service, of the danger they faced. But it wasn’t enough.

“If we are leaving our countries, it’s because we can’t be there anymore. We risk our lives by crossing two borders to be able to enter the United States. But they keep sending us back. I’m about to have my fourth court date and not for one moment have I ever felt hope that the judge will let me in.”

Part Four

Trapped in Tijuana: Life Under The Migrant “Protection” Protocols

Asylum seekers sent back to Mexico under U.S. immigration policy face danger, discrimination, and dire conditions.

TIJUANA, Mexico — Julio Gutierrez, his wife, and their teenage daughter fled Nicaragua after being targeted by government-backed paramilitaries. In 2018, protesters filled the streets of Nicaragua demanding that President Daniel Ortega resign. In response, Ortega's administration outlawed demonstrations and began imprisoning those involved, accusing them of inciting disorder and criminal behavior.

“I was designated a target by the paramilitaries,” said Julio. “I was persecuted, harassed. One day they followed me and said, ‘If you keep supporting the university students, you’ll disappear.’”

Julio hoped to find safety in the United States, where his uncle had offered him a place to stay. But upon reaching the border, he learned that he would have to remain in Mexico under the Trump-era policy known as Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP. Now, the family lives in a shelter on the outskirts of Tijuana, waiting to begin the asylum process.

“You see a lot of kidnappings, a lot of death. I don’t see [Mexico] as a safe country,” Julio said. “If I’m fleeing from an unsafe country, why would I stay in one that’s worse?”

Implemented in 2019, MPP forced tens of thousands of asylum seekers to remain in Mexico while awaiting their court dates in the U.S. In its first year alone, more than 1,000 reports emerged of rape, kidnapping, torture, and other violent attacks against those in the program—a figure that likely undercounts the true scale of abuse, given Mexico’s high rate of unreported crime.

As of March 2020, nearly 65,000 people had been returned to Mexico under the policy. Many were sent to border cities like Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, Nuevo Laredo, and Matamoros—areas the U.S. State Department warns Americans to avoid due to violence and kidnappings.

In Tijuana, asylum seekers wait an average of six to nine months just to begin the application process. A survey by the U.S. Immigration Policy Center found that 35% of migrants waiting in Tijuana were threatened with physical violence. Of those, 67.5% were subsequently attacked.

Julio and his family have spent more than half a year waiting for their court date. During that time, they have barely left the shelter.

“The process is long and difficult. We don’t have any resources—no money, no jobs. And my daughter isn’t in school,” Julio said. He fears for her safety. “She’s reaching puberty. We don’t go out because we’re afraid someone could snatch her away. I already put my wife and daughter in danger once. I don’t want to do that again.”

The family stays at Misión Evangélica Roca de Salvación, a shelter housing 67 asylum seekers from Mexico and other countries. Some were brought by Mexico's immigration agency; others arrived on their own. Though the agency continues to refer new arrivals, it no longer provides funding.

“We’re always short on supplies,” said Juan Carlos Espinoza González, a shelter employee. “Right now we’re out of eggs, milk for the kids, and diapers in several sizes.”

Since 2018, the shelter has relied solely on donations. But its distance from the U.S. border means it receives fewer supplies than shelters downtown. To survive, it charges residents who can work 200 pesos (about $10 USD) per week to help cover costs.

For many residents, even that small sum is hard to come by. Fear of leaving the shelter is common, and those who try often face rejection.

“It’s really hard being in Mexico where people know you’re a migrant,” said María Gómez, a Guatemalan asylum seeker. “You go to look for work, and as soon as they hear your accent, they say, ‘You’re Central American.’ They discriminate against you.”

At her former women’s shelter, she recalled contractors coming in to offer jobs—but only to Haitian or African migrants. “They refused to hire us,” she said.

Anti-Central American sentiment has grown in Tijuana since the arrival of migrant caravans in 2018. That November, the U.S. temporarily closed the San Diego border, causing major disruptions and frustration among local commuters. Tensions boiled over when a group of migrants attempted to cross the wall, sparking clashes between protesters and residents.

Tijuana-based journalist Omar Martinez witnessed the confrontations firsthand. “A group of people from Tijuana marched toward the migrants, waving Mexican flags and chanting slogans. People started yelling, fighting. It was chaotic,” he said. “It was a sad day. We’re not like that. We usually help migrants.”

But those tensions haven’t disappeared. Julio said he’s been turned away from jobs solely because he’s Central American.

“Mexicans see us like we’re criminals, like we carry the plague,” he said. “I’ve tried to get work so many times. As soon as they find out I’m not Mexican, they slam the door.”

Part Five

Asylum Seekers Struggle for Due Process Under ‘Remain in Mexico’

With legal aid out of reach and court dates dragging on, asylum seekers like are forced to navigate a broken system alone—or give up altogether.

“So, what are you all going to say if the judge tells you that you need to bring a lawyer to your next hearing?” Mateo Jimenez asked, scanning the faces of asylum seekers seated on folding chairs inside a Tijuana legal aid center.

A woman in the back raised her hand. “Is it true what you said about American lawyers not coming to Mexico, and Mexican lawyers not being able to go to the United States?”

Jimenez didn’t answer her question directly. Instead, he delivered a courtroom-style correction.

“I am asking you a question and I want you to respond directly to what I am asking you, because that’s going to help you in court. For example, a judge asks you is it black or is it white? You can’t go telling him ‘uh…um…it’s kind of brown.’ No. It’s black or it’s white.”

His delivery was forceful, but it reflected the stakes. In only two hours, Jimenez, an immigration attorney based in Tijuana, had the responsibility of preparing dozens of asylum seekers for one of the most consequential appearances of their lives. Most will face the judge alone, without any legal representation.

Because of the overwhelming lack of legal aid available to asylum seekers placed into the Migrant Protection Protocols, or “Remain in Mexico,” Al Otro Lado Legal Clinic holds bi-weekly “know-your-rights” trainings like this one. Volunteers explain everything: what time to arrive, what to wear, how to address the judge, what to expect inside detention, and how to prepare for hearings without a lawyer.

Maria Gomez attended one such training after being instructed during her initial court appearance that she would need to return with legal representation. She received, along with her Notice to Appear, a list of pro-bono legal service providers allegedly available to assist with her case.

But the list was printed in English. Most of the organizations listed didn’t serve the San Diego region. And when we called every number on the list, not one was able to provide legal services to asylum seekers currently residing in Mexico.

“They expect you to show up with a lawyer,” Maria said. “But none of the lawyers they give you have time, or they don’t answer. And we don’t have the resources to pay for one in the U.S.”

According to Department of Homeland Security data, just 6.6 percent of asylum seekers assigned to the San Ysidro Port of Entry court had legal representation. Nationally, the rate was 6.1 percent. Of the nearly 65,000 people placed into Remain in Mexico between January 2019 and March 2020, only 517 won their cases—an asylum grant rate of 0.8 percent.

Representation drastically increases an asylum seeker’s chance of success. While only 0.4 percent of unrepresented individuals were granted asylum, those with lawyers prevailed in 6.8 percent of cases—making them 17 times more likely to win.

Still, for many, even reaching a courtroom is difficult. An internal report by the U.S. Immigration Policy Center noted that Remain in Mexico caused widespread “defective notice of immigration court hearings,” in addition to “tent immigration courts that raise serious due process concerns” and “issuance of in absentia removal orders... when asylum seekers do not attend.”

For those who do make it to court and express fear of remaining in Mexico, judges may refer them for a “credible fear interview,” the only legal route for removing someone from the program. But a Human Rights First study found that only 25 percent of immigration judges actually ask about fear of return, despite DHS’s legal obligation not to return anyone at risk of persecution.

Luisa Martinez hoped that court would be the place where someone would listen. At her first hearing, she planned to explain that she and her two young daughters had been nearly kidnapped in Mexico. Instead, she was handed a new court date three months later and returned to Tijuana without being allowed to speak.

“They didn’t give me the chance to say what has happened to me in Mexico,” she said. “They don’t give you a chance to express what you’ve suffered, the danger you’re in in these places.”

Luisa showed up again for her second hearing, only to be sent back once more. After that, she gave up and returned to Honduras—despite the very threats that had forced her to flee.

“For asylum seekers placed into the Remain in Mexico program, the process is not just disorienting—it can be decisive,” said one former asylum officer. Individuals denied asylum by an immigration judge can be barred from entering the United States for five years. “One mistake—one missed date—can cost you everything.”

According to DHS policy, immigration officers are required to ensure migrants “fully understand the proceedings against them.” The standard is explicit: the officer must be “absolutely certain... that the alien has understood.”

But that promise breaks down in practice. Much of the information asylum seekers receive is in English. Form I-867, which includes questions about fear of return, is often presented without adequate translation. Migrants are required to initial each page and verify their responses—even when they don’t understand what’s written.

Maria, who fled Escuintla, Guatemala with her son after gang threats, thought she had made her fear clear to border agents. But when she showed me her signed transcript later in Mexico, her answers said the opposite. The paperwork claimed she did not fear return to Guatemala and had no fear of persecution.

When I read her the same questions in Spanish and asked her to respond exactly as she had in the interview, her answers were unequivocal: “Yes, I’m afraid.” “Yes, I would be harmed.”

“I never said that,” she told me, stunned.

Talia Rodriguez also refused to sign her paperwork. After four days in CBP custody, she was told she would be returned to Mexico. When handed a document to sign, she asked what it was.

“They didn’t give me the opportunity to read anything,” she said. “I asked what would happen if I didn’t sign. He told me, ‘Either way we’re going to turn you back.’”

She declined to sign and was returned to the holding cell. By morning, she was on a bus back to Mexico.

Customs and Border Protection agents often ignore asylum seekers’ requests for fear screenings. A UC San Diego study found that six out of ten people who told CBP officers they feared returning to Mexico were still placed into Remain in Mexico without a proper interview—violating the international legal principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning people to countries where they face harm.

Even when screenings are conducted, the evidentiary standard required to pass is almost impossibly high. DHS guidelines require that asylum seekers prove they are “more likely than not” to face persecution in Mexico—a threshold typically reserved for full immigration hearings, not brief interviews conducted in detention centers without access to counsel.

“This mismatch between the high evidentiary standard and the inadequate procedures all but ensures violation of the non-refoulement obligation,” a coalition of asylum officers stated in an amicus brief filed with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

That’s the environment people like Talia, Maria, and Luisa are forced to navigate: without legal help, inside tent courts, in a system where the odds are overwhelmingly against them.

In July, the Mexican government began offering free buses from the US-Mexico border to its southern border with Guatemala, targeting asylum seekers like Luisa who chose to abandon their claims and return home. Weeks earlier, Mexican airline Volaris launched a program advertising one-dollar flights for Central American migrants, reportedly to help reunite families. But multiple reports indicate that some migrants placed into Remain in Mexico have been coerced onto these buses and planes without clear consent, leaving them thousands of miles from their court dates and without a way to return.

From Tapachula to Tijuana, asylum seekers faced more obstacles to applying for protection in 2019 than in any recent year. Policy changes by both the United States and Mexico have raised concerns that the two governments are relying on deterrence strategies aimed at discouraging people from pursuing asylum altogether.

A closing reflection from Talia Rodriguez, who remains in legal limbo after multiple court dates:

“After being released from detention, there were only about seven of us, of the original twenty, left. Most people said they were going to return to their countries because they knew they were waiting in vain. They said, ‘We aren’t going to wait for something they’re never going to give us.’

If we are leaving our countries, it is because we cannot be there anymore. We evade the fear we feel knowing that Mexico is dangerous. We risk our lives by crossing two borders to try to enter the United States. But they keep sending us back. I am about to have my fourth court date, and not for one moment have I ever felt hope that the judge will let me in.”

Post a comment